Injecting the Joy: A Critical Conversation with Mahogany L. Browne

Mahogany L. Browne is an activist and artist.

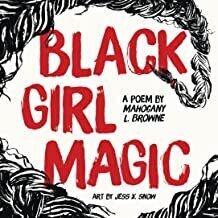

For the last two decades, her work has revolved around an insistence that Black lives and Black women and Black girls and families be not only seen but celebrated, protected and compensated. She has amplified that message through her own work as the author of six collections of poetry and three children and young adult books, including Black Girl Magic, Woke: A Young Poets Call to Justice and Woke Baby. She has championed that message through editing collected works by other authors, and by leading and curating programs for institutions like the Ford Foundation, PBS, Pratt Institute, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, Urban Word NYC, Bowery Poetry Club, Cave Canem, Mellon Research and the list goes on -- she is dedicated and decorated.

As Woke Baby declares: “Like a good revolutionary, she never ever sleeps.” She is prolific both in her work and art, and perhaps more importantly, in the spaces she is building for others to create their own. She is one of the most vital activists working in America today, and we will be teaching her work, her pedagogy and her love to our grandchildren decades from now. I sat with Mahogany last week to discuss parenting, healing and activism during this fragile and difficult moment. Our interview has been edited for clarity -- full audio version available.

This landing page is a part of our learning stream ‘For Black Parents’ and contains additional resources linked throughout the page. If you are not current subscribed to this learning stream, you can access it inside of Crescendo by typing /crescendo to the bot and selecting ‘For Black Parents’ as a topic from the ‘preferred topics’ section.

Mahogany thank you so much for your work, and thank you for taking a few minutes to speak with us about it. How are you today? What’s on your mind and where would you like to ground us first?

Today is one of those interesting days. It’s a small lull, and those don’t come often. I just made sure to prepare myself for today. I made sure not to turn on any news, not to go to the twitter feed, and just keep myself grounded for a couple of moments before having to, you know, activate. And engage, yet again, in the work. It’s constant. But I’m here. And I am inspired. And as soon as we get off this call, I’ll see what work needs to be done.

I’m always scared and energized and sad -- and of course I have my daughter who is a burgeoning activist herself, and her awareness makes me far more tapped in than one would think you need to be because not only am I processing information for myself and community, but I’d also like to be able to talk to this young person about the vastness of the things that are happening. I don’t know if that answered the question, that was a whole scope of all the feelings. (Laughter)

Of course it does! It’s a beautiful grounding. And I’m glad you brought up your daughter too. So much of your activism is space-making for others, including people like your daughter, and your chosen daughters and the beloveds you’ve welcomed into your life as a leader.

I’m interested in a theme that runs thematically throughout your work. What does Black Girl Magic mean to you, and why has this become such an anchoring thesis for so much for your work?

Black Girl Magic stands for resilience. It is all the ways in which a Black girl, Black woman, Black trans person, Black femme, can be unequivocally unshakable. Right? Your being is unfettered. Your brilliance is unwavered. Your integrity is unquestioned. You belong in every room you decide to go into. And that is why I’ve been building spaces (or trying to keep spaces open to people) that have been closed out for far too long.

That is the resilience that I am always turning to and trying to honor. When I think of Black Girl Magic, I think of all the ways I get to live and be because of pillars like Ida B. Wells, because of Ntzoke Tzonge who said, in the 70s, where there is Black womanhood there is magic. Where there are women, there is magic. She thought of that before we trademarked it and started making t-shirts. She thought of it before this work happened.

Thank you for this. I’m glad you’re bringing up voices like Ida B. Wells and so many other folks who I know your work is grounded in. You recently wrote the introduction to Penguin Random’s reprint of Lorde’s iconic Sister Outsider. I was hoping that if I read a small sample for your introduction, just your words back to you, you might be able to use that as a springboard to speak back to Ms. Lorde.

You say, “I believe Lorde penned these essays to explain the world to our children. Man Child, a selection I return to know in a time of absolute terror, it especially rings true. “If they cannot live and resist at the same time, they will probably not survive.” And who are we to die without a purpose or a fight? This book instilled a hope, an expectation I didn’t realize was my birthright. Sister Outsider is an heirloom for our children and our child selves. These writings passed down to each of us hold the power of information. Each of us holds to our chest what solidifies our understanding of our place in the world.”

Wow, I said that?

You said that. You sure did, you sure did.

Listen, Audre Lorde is one of those writers that I did not know I needed. I had learned of her work before I went to my MFA program -- “Your silence will not protect you,” master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house, you know the quotes, right? And then of course there were the poems and the essays I returned to. But when I encountered her “Open Letter to Mary Daly” I just felt it was the most giving read. She was saying, like: I won't’ let you off the hook, and I’m going to be generous and write down this moment, where people are always asking, “How can I do better?” but they don’t really want to do better? So that was the generosity in her spirit, even as it became this thing that felt like a jab -- but sometimes you can’t hear someone who is telling you the truth unless there is a hurt or a burn to you. And that’s why I love that piece so much. It guided me in how I started having conversations because I was no longer afraid of hurting the feelings of someone who was never considering my own. Right? Why am I caring about how much you mean well, when your impact far outlasts and shatters your intention? Your impact is negative. I turned to Lorde for the first time at Goddard -- but then then when I got to graduate school I dove in a way that was ferocious. I was at Pratt Institute in the inaugural class of the writing and activism program -- which was the first of its kind in the nation -- and still, it was sullied with white supremacist action. You had people who were saying they were activists, but saying “Why can’t I say the n-word?” It was wild. So, Audre Lord is who I turned to because I needed an articulation. Because all I have is sadness and fire and anger -- that’s my go to. And I needed a different kind of ammunition.

And there was nothing of her there. I started realizing the libraries were full of more works by Foucault and Gramsci and there was nothing of her. And this means something. That the only Black woman text I can find in this institute is a novel by Toni Morrison. It was glaringly obvious what they were trying to school. So, it not being there meant I needed to read it. And she became my compass. And sure, I might lose some friends and opportunities, but I won’t lose my soul.

Her work is the counteractive agent to all of the conditioning that we have been taught about what we deserve as Black feminine mothers. I had to sit with it, I had to understand it and read it -- and when I had the opportunity to write the forward I was shook. I thought there was no justice I could do. I was deathly frightened. But then I also remembered that I wasn’t supposed to read Audre Lorde. They hid her from us. And if they hid her from someone like me? I knew that I needed to make her work accessible to people who come from where I come from. What kind of world will then happen? Then the revolution really begins, right? You have your blueprint, and your toolkit. You get to walk around with the right tools to fight a supremacist agenda.

Yes. I think that’s the right language. And in Lorde’s words, what if everyone was called to articulate without craft? Without reservation or fear of the structures that are set up to make us afraid? I love the notion of being “a threat knowing yourself,” and those are your words.

You talk about being a “purveyor of Black Girl Magic.” You’re also a purveyor of rituals for your own self-care, and preservation of your own magic and healing and joy. I am wondering if you might feel comfortable sharing a few of those practices.

Like any poet, my vice is books. I buy books that I haven’t even read yet, as you know. But a good meditation is actual meditation for me. Even if it’s five minutes with a timer. And it was difficult for me to learn how to do this. I started two years ago in Florida, and it was by mistake. I was just sitting there during a residency, waiting for the manatees to come out and just watching and counting the waves – and the next thing I know, the manatees showed up and I just started crying. And it was two things.

First, I'd never seen manatees before and that was magical. But second, I realized how much of my life had been spent just going. Just dealing. Just managing. There was never any time for me to process how I was feeling. There was never time that I gave myself to feel, or not feel, or just sit. I always felt mandated by productivity. Like, if I'm not doing something, what am I worth? And a lot of that comes back to gender norms, and me trying to prove that I am worth people's time, and energy, and investment, and attention. And that plagues me. And I think it will for all of my days because it is bedrock to how I learned myself as a child affected by the mass incarceration system, and feeling abandoned for so long from a parent I lost to addiction for over a decade, a father who I lost in the system and addiction for my entire life. In this way, I'm constantly engaging with these inadequacies through my work, and all of it, of course, is built around who believes in me. As if to say, if you believe in me, I can believe in myself, even though I should already believe in myself. So that meditation filtered all of this into a kind of wail. I could literally cry right now. It just kind of left me.

I am in the business of making people remember the unseen and unheard. Unseen and unheard are often ignored when you look like me and when you come from where I come from. The meditation is always a space of reclamation that reminds me I am supposed to be here. I am a good enough parent. I am a good enough writer. I am a good enough organizer. I am a good enough advocate. It's a constant reminder to clear the head of the doubts and the toxins… and then you can re-engage.

But also, fun shit it is okay. You get to watch Real Housewives of Atlanta. You don't have to dissect the entire world in 45 minutes. You can tap out. You have to. There is no extreme that doesn't burn you. We wonder why the fires in our lives can't be responded to dash – it's because we haven't exercised that muscle that reminds us to release. I learned in reading about Audre Lorde, Jane Cortez, and June Jordan that when we’re fighting physically for our lives, we’re holding internally all that muck, too, so you have to release it. If that's a cocktail, which I also love, great. If that's watching Legendary on HBO. If it's your spin cycle class. If it's laughter with friends. You need to inject that joy into your life. Because joy is the antidote. Don't let them steal it when you're doing all of this work.

And don’t call it guilty pleasure. Love it. I had to stop saying that.

A lot of readers and listeners that will find this conversation are parents also of Black children, and searching for support. You are an author that writes specifically for young Black voices and for families looking for ways to engage this idea of Black Girl Magic and beauty and blackness in the lives of kids. How do you think parents could be thinking about these conversations in ways that could be helpful for them right now?

The best quick resource I can offer is Black Girl Magic. Not only is Black Girl Magic for black families, it is for all families. One of the issues we’ve presented our young people with is that there is not enough diversity in their book choice, and in their worlds. When they see a TV show where there are all black kids, they say, “This all black show,” instead of saying, “This is a TV show worth watching because it is funny.” It has already been decided by the texts and stories we allow in their lives. While we all may not live in spaces where diverse playdates are possible, your books and your literary outlets are always there. It is your duty to allow your child to witness the world. Not to center themselves in it, but to bear witness to it. And that means as young as in the womb. I have a friend who was reading Woke Baby to his son when he was in the belly, and then when the baby was born that was the one book they read every week. And I just thought my god this is amazing that you understand this has to happen in vitro. It has to be always. It has to be part of our ecosystem every day. If it's not, that's how people go 10 years in the game and they’re like “Oh, I don't see color.” How is that possible? The world sees color. Kids don't, but kids don't have to -- because their parents do. It is your job, parent, is to ensure that you are leading your global citizen, who is ready to be a part of the world rather than just centering themselves.

Right. You're doing this now, but you also do this beautifully in your writing for young voices: You do not water down or simplify themes of anti-Blackness or sexism in ways that a lot of children's and young adult literature has a tendency to do. I'm wondering if you could just speak to that choice in your work, and what it means for you to speak at or slightly above the learning edges of where your readers might be.

What I learned real quick is that kids are much smarter than adults. Like, they got it. Have you seen a two-year-old play with an iPhone? (Laughter)

Do you know how long that took me? You know what I’m saying? Like, what the hell? These kids are brilliant, and we are playing ourselves. We are dimming their light, and we are stagnating their growth. Get out of the way.

My most recent book is called Woke: A Young Poet’s Call to Justice, and it is an anthology of poems that talk about the building foundations of social justice ideas. What does it mean to be “woke?” What is stereotyping? What is allyship? What is protest? What is ableism? What is immigration? How do you talk about these things with an 8-year-old? I realized that if I want to talk about restorative justice to a kid, maybe we need to start talking about empathy. Maybe we should start talking about forgiveness. You know what I’m saying? Because what's really clear is that the people in congress never had these conversations. They don't know what empathy or compassion are. They're dealing with numbers and investments and votes for all kinds of shoddy things. What if we started talking to them early in ways that ask them to think about what forgiveness means? This is how the world works. And kids know that right now. When it's lost it’s because we are not consistent enough as a community, because what we are saying is, “Do as I say, not as I do” -- and we know that doesn't work. Let's speak it plain, and keep it funky with these young people, because they are brilliant. And at the end of the day, more times than not, it is adults that are messing up the conversation.

And sometimes we have to study ourselves. We have to relearn. How many times have you had to relearn how to do math problems? Like, okay let's talk about algebra because I ain’t touched it in... forever. But you have to relearn it, and you have to exercise that muscle. The same goes with being a community-centered person. The same goes for understanding differences and calling yourself to the mat. It is okay to be uncomfortable. We are so busy trying to make sure that our young people aren't uncomfortable with hard conversations that we are removing them from the dialogue.

I love the notion of returning to hard conversations as a muscle. And the idea of relearning algebra is a really good example, because sometimes when I realize I need to brush back up on something I sometimes also realize I never learned it in the first place. In other words, I’m confronted by the possibility that I may have just sort of skated through or cheated that class the first time around. And now that the world is calling for it, or I have to explain this moment to the young people in my life. I have to confront the reality that I never learned what they're asking in the first place.

Yeh! I just kind of got away with it. Because nothing was at stake then, right? What was really at stake? You got by this far but look at what that has caused for our communities. You have such a hard time having a conversation about gentrification that you are unable to implicate yourself as part of the problem. It has to be more than words. It’s got to be action -- and some people will never be ready for that.

Well that's the space we're at right now, with so much. Reparations discussions are the entrance ticket to talking about white fragility and shame and guilt. Not the end result. Not the trophy.

There’s no trophy. No participation points. I know this is the worst thing to say, but I don't care about an anti-racist worksheet. Anti-racist booklists are simply not enough. They are simply a guide to beginning. And if you look at that list and think your work is done, not only have you played yourself, but you are disrespecting the work that goes into building curriculum. And building movements. You would never look at a teacher and say “Yeah, yeah yeah. Thanks for that. But can I just get the quiz?”

Any work around anti-racist anything has evolved around white people's comfort-level and capacity to engage with it. I worry that so much of it is turning quickly into a soft, self-congratulatory space where people feel like the permission to engage in white shame and white guilt and white fragility without acknowledging up front the need to redistribute resources. People are very quick with a hashtag and very quiet when we start talking about the redistribution of wealth. And the field of anti-racist work, quite tragically, has never accurately positioned reparations as it's pillar, and I think we feel that and see that now that more white people are coming to this kind of critical thinking.

It’s a brave new virtual world now. And you, Ms. Mahogany L. Browne, are extremely active in the online space. Before pivoting to the future and projects you’re working on I'm wondering in this moment, when there is so much chaos and violence and grief constantly online, how are you managing to live and work in the virtual space in a way that allows for healing for you?

Remember those two words I said at the beginning? It is okay to tap out. that tap out is crucial. There are days when I am not going on to ig or twitter because now that we have all this information, it is never ending. There are so many videos of police brutality incidents that I have not seen. At this point, I've muted those videos. That shit is PTSD. So, I have to assure that I am engaging in a way that doesn't feel like I am harming myself online. I actually think that they have become a tool of distraction for those who are doing the work. I think it's necessary, and I would never say don't post it or whatever because I understand that these videos are how we are finding out about most of it -- and I say “us” as a nation and world of people, but there is an “us” that has always seen it. Right? There is an “us” that lives next to it, and we are not surprised. The people that are surprised are those who have been shielded from it for so long. I'm allowing myself to tap out.

I am also following people who are doing the work. What are you doing and how can I assist? I love that. That's a great game to play. If you are not the protesting type, are you a petition signing type? Are you going to share that petition? Are you donating money? Are you ensuring that people are getting food? Are you ensuring that medical supplies are showing up? That's where I am, at this point. Whoever is doing the work, how can I assist?

And of course I'm writing, but sometimes the writing gets a little heavy, so I've turned to creating this online audio vigil called “The People’s Vigil.” It is about two dozen folks throughout the world that I just asked to read 40 + names -- mostly names we do not know about. In 16 months, we've had over 1,608 gunshot victims through police brutality. And this is not hand-to-hand combat between people on the streets, this is state-sanctioned violence. And they've gotten off, and they’ve gotten paid, and they're still working, so when someone putting their knee on someone's neck surfaces, you realize they've already had all of these. You have a scroll. This is a marker to help us look at those who are getting lost in time and space who didn't have a video, or a family. You say their names. The vigil exists. And to see it now existing as this archive is so powerful, and so moving. The money that we raised, we donated to folks in need -- we put money into twelve different states’ bailout funds during the intense stretches of the protests, we sent medical supplies, we paid for a hundred different families to get food in Brooklyn from a Black-woman run farm stand. I felt like I was doing something slightly different but also a part of the wheel and supporting those folks who are on the ground stomping. Everybody has a job, and you've got to figure out what yours is to assure that you aren't just resting on your laurels while people are out here fighting for freedom.

You talked about The People's Vigil, which we've linked to, along with other resources you’ve mentioned. What other projects are on the horizon for you? What can we draw attention to or shout out?

Well I just finished my first young adult novel which comes out in January with Crown Books. It’s called Chlorine Sky, and it is about a girl dealing with fractured friendships, basketball and gender norms. I also have a book-length poem, and that's called I Remember Death By Its Proximity To What I Love The Most. That project is investigating the impact of mass incarceration on women and children, i.e. my own story. Then following that, I have a book of essays about mass incarceration, and that’s something you can find information about on the Academy of American Poets’ website.

It’s a lot. But I'm here. And I'm happy to be here. I was affected by the coronavirus. I contracted it within the first three weeks of quarantine just going out on a walk. After being knocked out for ten weeks, after being that close to death, there's nothing else I can do but make sure our stories are remembered, and that I do my part. So however that looks, whatever it looks like, I'm doing it. And I ain't got time for much else.

You are more than doing it. And you are more than doing our part. Mahogany I'm so grateful that you've taken some time to chat with us about your work in a moment where people are hungry for direction and looking for anchor. We're all looking for reasons to not attach our sense of self value in the world to being overwhelmed. Are we doing enough? Are we running around? How does a protest look? How do we show up? Your work is a great reminder that who we are and how we love ourselves doesn't need to be tethered to that. Our world is richer because you're in it. Thank you for your ongoing work. I’m glad you’re healthy. Anything else you'd like to offer?

Nope. Stay free.

Stay free. Thank you, Mahogany. We love you.

Love you.